How to be a refugee, with mushrooms

Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe shares insight into the refugee experience, and how to leverage permaculture and mushroom farming for self-reliance

Reading time: 13 mins (grab a cup of mushroom coffee)

If you’re reading this via email, it may be clipped at the bottom. Click here to read the full piece ✌️

🏆👏 Quick announcement: Congratulations to We Were Here, a documentary contributed to by Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe, creator Gaz Oakley, toymaker and Syrian refugee Mohammad Hussein Waheed Asaf and UNHCR, which has just won at the Webby Awards in the ‘People's Voice Winner’ category!! Well deserved 👏🏆 Watch the documentary here.

Ok, on to the article…

Arriving.

Arriving in Rwamwanja refugee settlement in southwestern Uganda, I’m hit with the familiar feelings of awe, admiration and respect; coupled with guilt and revulsion for the Western lifestyle I’ve traveled from—so far removed from the food on our plates and the waste we create. These feelings are not new, but renewed and lingering; visiting Hodari Foundation in Kyaka II earlier this week was a catalyst and our current visit is intensifying them, as Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe, Founder and Director of NGO Rwamwanja Rural Foundation, welcomes us into his permaculture palace.

Every space is maximised. In the courtyard, bamboo offcuts are ready for milling. Crates, buckets, barrels and trays are bursting with seedlings. The roof of a mushroom grow room is neatly thatched with locally abundant grasses.

In the extended back garden linking Bemeriki’s neighbours, my sound guy and I are given a grand tour of abundant edible and medicinal plants thriving in the tropical climate: amaranth, sunflowers, tomatoes, papaya, cassava, bananas, matoke, Madagascan beans, onions, leeks, passion fruit, okra, nasturtiums…I lost track of the medicinal plants we nibbled on while strolling through this paradise.

Spent mushroom substrate feeds the vegetables. Corn husks decompose into tasty mushroom food and to make bio-char briquettes in a carboniser. A mountain of compost is a training ground for permaculture learners and ten beehives produce honey. Lastly, we’re invited into the spawn lab where upcycled Uganda Waragi gin bottles are growing grain spawn for oyster and shiitake mushrooms.

I’m overwhelmed and struggle to do justice to this complex web of interconnected activity, as intricate as the mycelial process itself.

“Nothing goes to waste. Everything is used. My garden is healthy, and I am healthy. Everything here is medicine as well as food. Nothing goes to waste.”

- Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe, Founder and Director of NGO Rwamwanja Rural Foundation

Meeting Bemeriki

Meeting a great human can be a profound and transformative experience. Meeting Bemeriki was one of those moments. His undeniable presence, meticulous attention to detail and philosophical understanding of natural process and systems commands attention and respect. He speaks with conviction and confidence yet displays humility, empathy, vulnerability. Hear it for yourself in our podcast chat.

Bemeriki runs a youth refugee-led non profit organisation, established to empower young people living with refugee status to fulfil their potential and transform their lives. Rwamwanja Rural Foundation (RRF)’s aim is “to ensure these communities can restore local ecosystems, increasing climate resilience and biodiversity, while benefiting from regenerative agriculture activities that improve access to nutritious food. It brings together permaculture, Indigenous farming techniques, local languages as well as modern, affordable and easily accessible digital technologies to enhance reach and overall impact.”

They are achieving all of this through vocational training, permaculture and mushrooms, with a mission to make highly nutritious ready-to-use food products more accessible and affordable to those who need them most.

“We believe that if the roots of a tree are affected, the trunk and also branches, leaves and fruits are affected.”

- Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe, Founder and Director of NGO Rwamwanja Rural Foundation

Why should you care about this?

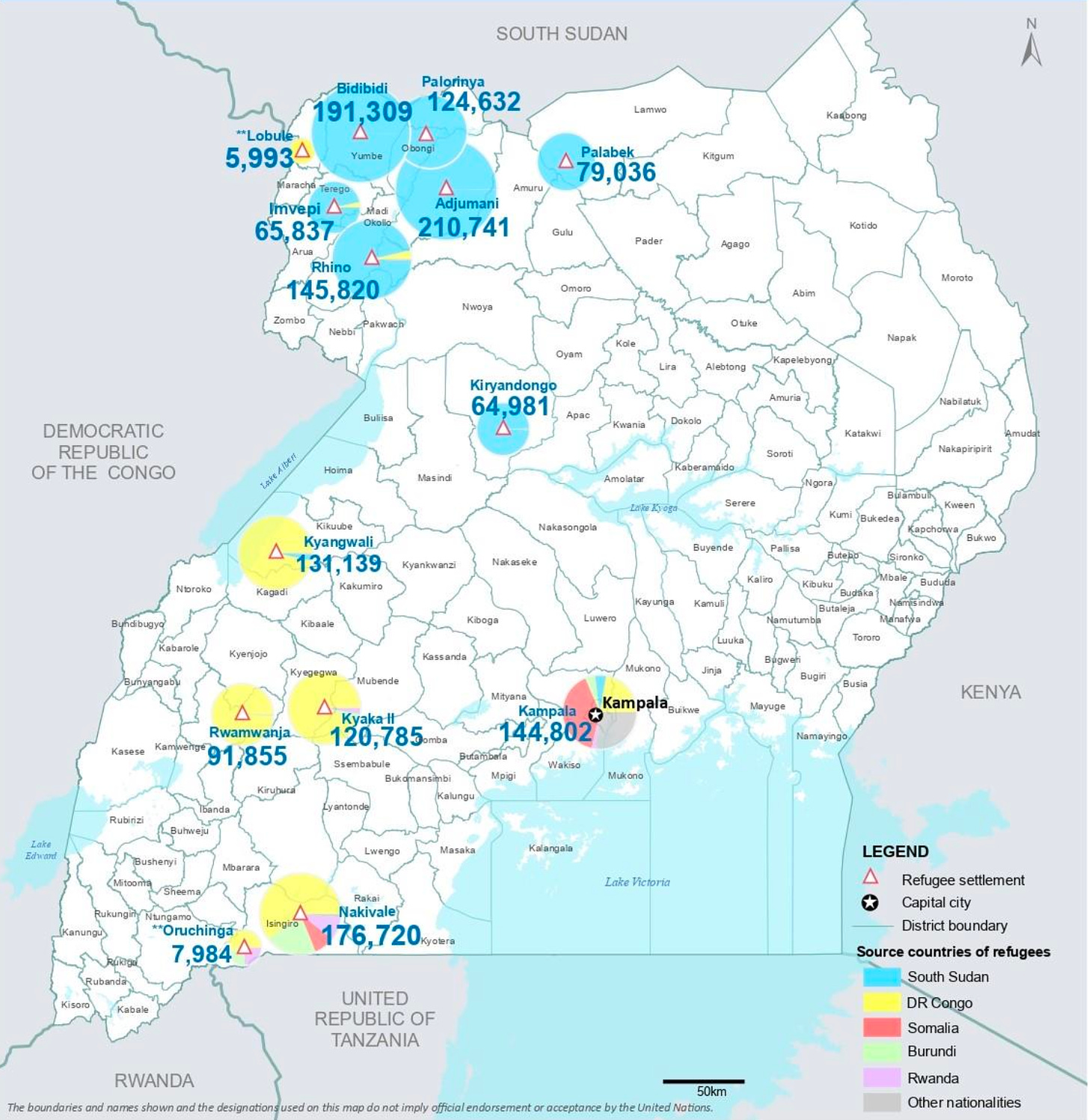

For context, Rwamwanja refugee settlement is home to ≈92 thousand refugees, most fleeing a decades-long conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The conflict is complex and multi-layered but the heart of the issue is the world’s ever-increasing demand for advanced electronics. The Council on Foreign Relations reports, “As the world has become more reliant than ever on cobalt, copper, zinc, and other minerals, local and external groups have become more incentivized to get involved in the Congolese conflict.”

For readers who may be thinking, “this is a not my issue”, think again: these ‘conflict minerals’ likely include materials needed to produce your smartphone, laptop, gaming console or EV battery.

We are all complicit until this issue is resolved.

Settlements are becoming homes

With the DRC conflict intensifying, the amount of asylum seekers and refugees are increasing by the day. Settlements like Rwamwanja (more than 50 square km in size) and Kyaka II are becoming permanent homes for people unable to return to their home lands.

Bemeriki has lived away from his DRC home for 18 years. He speaks 17 languages and has visited 15 African countries in a bid to research and understand the refugee lived experience—knowledge he now shares to increase his community’s capacity for self reliance without having to depend on external aid.

“We didn’t choose to be refugees. Nobody thinks of becoming a refugee. That’s why I try... whoever I sit with, I sit and explain how life as a refugee is. I advise them on how they can live.”

- Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe, Founder and Director of NGO Rwamwanja Rural Foundation

How to be a refugee: the challenges

Once past the initial challenges in early-stage resettlement—access to basic necessities like adequate shelter, clean water, food, healthcare—people are faced with issues like:

Where do you set up home? How do you earn a living? How do you feed your family with nutritious and delicious food? How do you overcome language and cultural barriers? How do you navigate threats of crime, exploitation and xenophobia in the host community? How do children access quality education? And much more.

For RRF working with people at high risk of hunger and malnutrition—and often the most vulnerable such as those with disabilities—these challenges have only been exacerbated by cost-of-living increases caused by the pandemic and Russia-Ukraine war.

While many refugee aid organisations, NGOs and government agencies provide support, major players like the World Food Programme and UNHCR have a major funding deficit.

TL/DR: not enough money, not enough aid.

‘Refugee’ is not an identity, just a status

In the face of extreme challenges, people who find themselves with refugee status often need to take control of their own circumstances. (I’m intentionally saying ‘with refugee status’, because ‘refugee’ is not an identity, just a status.)

For Bemeriki, this has meant upskilling himself to grow food, use the resources available to craft a viable lifestyle. In our interview he shares that he has refused to let the definition of ‘refugee’ define him or the circumstances of his family; rather shifting focus to his mindset and abilities.

As the day goes on I’m a lucky witness to how this mindset is rubbing off on the next generation: his 4-year old daughter is ever-present, observing her dad and endearingly mimicking his tendency to get ‘stuck in’ and handle things.

“We don’t know where we are heading. Tomorrow we may be taken back home, or there might be a decision to be locally integrated.”

- Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe, Founder and Director of NGO Rwamwanja Rural Foundation

Permaculture principles in practice

Bemeriki embodies self-reliance, dedicated to the practice of permaculture: an antidote to destructive agriculture (permanent + agriculture = permaculture) and a modern process based on ancient indigenous wisdom that’s guided by twelve principles and three ethics—earth care, people care and fair share.

Like nature and mycelium, permaculture is not so much a ‘thing’ as it is a process: a design process. I don’t have a permaculture garden, my permaculture is happening.

This idea rings true to the more attainable ambition of progress (as opposed to the unattainable perfection), as displayed by the day-to-day progress of Rwamwanja Rural Foundation’s activities and their impact on the community.

Mushrooms and People Care

People care is about looking after self, kin and community. RRF enables people to grow through self-reliance and personal responsibility by teaching them to grow vegetables, oyster and shiitake mushrooms.

We sat down with mushroom farmer and permaculturist Ngaragaje Uwamungu Daniel, who shared that he enjoys permaculture. After the war forced him to flee his home in DRC, settling in to a new life wasn’t easy, and learning to grow his own food has vastly improved his family’s living conditions.

Mushrooms are delicious and nutritious. The World Food Programme (WFP) supports pregnant women and young mothers in Rwamwanja with complementary breastfeeding porridge. Imported from Canada, Australia or the US, these products can be pricey, and mushrooms can be grown locally.

Rwamwanja Rural Foundation incorporates oyster mushrooms into their own mushroom porridge using local waste materials, further supporting the nutritional needs of pregnant or breastfeeding women and growing babies.

“Why can’t we teach our women to use what they have, so that they are not suffering from malnutrition and reducing their dependence from WFP? That’s how we came up with making porridge from mushrooms.”

- Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe, Founder and Director of NGO Rwamwanja Rural Foundation

Mushrooms are a great income generator. RRF has designed a value-addition model: while 1kg fresh oyster mushrooms sells for 6,000 UGX (Ugandan Shillings) or roughly $1.70, once those mushrooms are dried and powdered they retail at significantly higher prices per kilogram (70k UGX / $19.00 and 100k UGX / $29.00 respectively).

Dried and powdered mushrooms are transformed into products like mushroom porridge (for example, to supplement breast milk), mushroom coffee (just add hot water), mushroom powder (add a teaspoon to sauces for extra flavour & nutrition), as well as a mushroom tincture line in-the-making.

“After learning how to grow mushrooms, life is easier than before. I get money from mushrooms, and I can buy essentials for my kids. If I sell 3kg of mushrooms we can eat meat. If there is no cooking oil in the house, we can sell mushrooms and buy cooking oil.”

- Ngaragaje Uwamungu Daniel; Mushroom farmer, permaculturist and member of the Refugee Mushroom Growers Association; DRC national living with refugee status in Rwamwanja refugee settlement, Uganda

Mushrooms and Earth Care

Mushrooms at RRF grow in a closed loop system with zero waste. Substrate comes from locally sourced agricultural waste (corn cobs, cotton husks, banana leaves), while spent mushroom blocks are composted and fed back into the vegetable garden.

To demonstrate the extent of RRF’s earth care practice, Bemeriki takes us on a short drive outside the settlement. Leasing a piece of farmland in the lush Ugandan countryside, he is designing a permaculture and ecotourism learning centre: “Teach, Grow and Share”. The centre will teach permaculture and share this knowledge with the local community—essentially growing together.

The setting is idyllic: in the picturesque greenery, Bemeriki’s ambition is to build the space with the help of volunteers, starting with eco-pod shelters overlooking catfish ponds. The idea is to enjoy the tranquility of birdsong and frogs, after a day’s work helping to install solar panels for water filtration, build the centre’s banana plantation, raise rabbits (who’s waste will feed the fish), grow vegetables, alfalfa, sugarnut and napier grass (for local cattle farmers and to feed the fish at night), and maintain the existing Irish potato crops.

The entire thing is brilliant. It’s hard not to pack up a life in London in favour of volunteering here: contributing, building, learning, practicing. A dream.

“We teach people, we grow and we share with the rest of the community, so it goes around the three ethics of permaculture.”

- Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe, Founder and Director of NGO Rwamwanja Rural Foundation

Mushrooms and Fair Share

Mushrooms can facilitate cultural connection. Fair share is all about taking what we need and sharing what we don’t; giving a fair share of the bounty to others in our community.

For refugees in Rwamwanja, integration with the host community (i.e. Ugandan nationals) is crucial to overcoming language and cultural barriers which threaten safety and security, plus opening up economic and social opportunities. Particularly important as refugees are utilising valuable land that has been owned and managed by Ugandans for generations.

The local OPM (Office of the Prime Minister, in charge of refugee management alongside UNHCR), declared a mandate for all refugee activity to benefit refugee/hosts in a 70/30 split (for example, if you’re training 30 people, 7 should be Ugandan and 23 refugees). RRF takes this further: in consideration of fair share the organisation practices a 50/50 split. RRF’s board of directors are 2 refugees and 2 nationals. The organisation speaks the same language, spreads the same permaculture principles and shares the same cooking recipes between refugees and Ugandans.

Now, Bemeriki chuckles as he describes a more integrated community, overcoming old stereotypes and misperceptions and embracing inter-cultural marriage and trade exchange. Daniel’s kids speak their mother’s Swahili, Ugandan languages Runyankole and Rutooro, and the basics of their father’s French.

Communal training, knowledge sharing and an equal part of the financial mushroom pie keeps the host community included, fostering good relationships and helping to build bridges.

“No matter what I have achieved, it does not prevent me from continuing and achieving more. What I first hope to achieve is to make sure that households have access to food and that every home has food on the table.”

- Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe, Founder and Director of NGO Rwamwanja Rural Foundation

Why mushrooms?

Mushrooms work well in the refugee context. They are inexpensive to grow, not tiresome, grow in less than 4 weeks, grow in agricultural waste, are healthy, provide food security and generate good income.

Mostly, they can be grown in a small space indoors: critical for refugees who are awarded a 30x30m2 piece of land on which to set up a house, latrine and small playground.

Daniel divulges how quickly mushroom hype spreads in the community, driven largely by storytelling—for example, that mushrooms help orphaned children to grow—and also (debatably) superstition; for example, that mushrooms increase vitality, improve sexual health and cure diabetes.

“At first my neighbours thought I was mad, they said ‘Ha! Can someone produce mushrooms? Because mushrooms grow in the garden. They are from God’. But God is here to extend and expand our knowledge. The community are so interested in mushroom production. They are asking me to teach them so that they can produce on their own. We are organising with Bemeriki to see how we can teach them.”

- Ngaragaje Uwamungu Daniel; Mushroom farmer, permaculturalist and member of the Refugee Mushroom Growers Association; DRC national living with refugee status in Rwamwanja refugee settlement, Uganda

Mushroom challenges

Growing mushrooms may work well in this context, but also comes with challenges.

To transport firewood and materials to site, Bemeriki relies on a 3-wheel tricycle to move 1 tonne of substrate at a time. A van or truck would significantly increase production capacity. Access to good quality grain spawn has been a challenge which Bemeriki is now attempting to overcome through his on-site spawn lab.

Daniel shares insight into water acquisition: his primary water source is a shared community borehole 500m from the farm. Needing up to 60l per week for his mushroom farm, he’s had to navigate accusations from neighbours about taking more than his fair share, and negotiate workarounds where neighbours share in his jerry cans. A JoJo tank to capture rainwater may help ease this burden.

The next challenge, scaling up, would allow the organisation to fulfill orders such as a recent ask from a German company for 300 1kg packets of mushroom powder per week—a demand that currently can’t be supplied. RRF is hoping to address this through certification and a Refugee Grower’s Mushroom Cooperation across multiple settlements.

“When the farmers generate and people get food at their table, on their plates, I feel happy. They have access to food, they have money, their children will go to school, and they will have better health.”

- Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe, Founder and Director of NGO Rwamwanja Rural Foundation

Bemeriki—in closing

Spending a few days with Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe of Rwamwanja Rural Foundation, was less a lesson in ‘how are mushrooms helping people’, and more a lesson in ‘how to be human’.

To wrap up our interview I asked him to share a closing statement:

“I request that whole world recognise that refugees are humans like others; being a refugee doesn’t mean that the mind shifts, it remains the same. The way the world perceives a person who is called a refugee... [shrugs and shakes head]. We are humans, like others. We have the same rights.”

- Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe, Founder and Director of NGO Rwamwanja Rural Foundation

His demeanour has instilled a profound transformation in my own personal mindset, connecting the processes of nature and human evolution and lighting a fire to be better.

Thousands of individuals, unable to return home and living with refugee status, need to eat and to live. Without the ability to rely on consistent or sufficient aid support, the a culture of resilience and self-sufficiency being instilled by Bemeriki and others like Hodari Foundation (supported by organisations like Nourish All and others) are non-negotiable.

My only hope is that those of us living in privileged Western cities can take inspiration from this, take a good hard look at our own consumption behaviour and do what is within our own power and capacity to support where it’s needed most.

Thanks for being here and mush love!

🍄❤️

How can you get involved?

Donation – Visit Rwamwanja Rural Foundation’s website to donate towards an initiative within the foundation that interests you (e.g. transportation of waste materials to mushroom production site, or post-harvest handling and processing).

Volunteering - Spend time building RRF’s permaculture learning centre and engaging in knowledge & skills exchange. Find out more by emailing info@rrfug.or or rwamwanjaruralfoundation@gmail.com

Support, follow, engage and share the amazing work of Rwamwanja Rural Foundation:

Check out the Rwamwanja Rural Foundation LTD on YouTube

Connect with Rwamwanja Rural Foundation on Facebook

Who else is involved?

By getting involved with Rwamwanja Rural Foundation you will be joining a growing number of partners, supporters, mentors and teachers, including Nourish All, Swisscontact, The Permaculture Education Institute, Regenerosity, Abundant Earth Foundation and Lush Cosmetics.

THANK YOU!!

🙏This interview took place during Running with Mushrooms’ Uganda/Kenya mushroom road trip in October 2023. Thank you to Bemeriki and Rwamwanja Rural Foundation for having us, and for their patience while illness and work commitments delayed the release of their story.

🙏Thank you to Samantha Koches of Nourish All for introducing us to each other, and for the never-ending support of Running with Mushrooms and the organisations we’ve had the pleasure of meeting in Uganda.

This was a heartwarming article that also highlights the struggles of refugees. I grew up with refugees all around me so I grew understanding their struggles better than most.

Anyway, I came here a mushroom story and got that and a lot more.

Thank you for such an informative article. Being involved with Nourish All, I have been educated on the value of mushrooms and permaculture. But your interview has greatly expanded my knowledge. Kudos to Bemeriki and all of the others who are donating their time and effort to helping others in need.